East Kootenay Ranchers Say Prime B.C. Grazing Land Is Wasting Away Amid Red Tape

Subhadarshi Tripathy

7/22/20252 min read

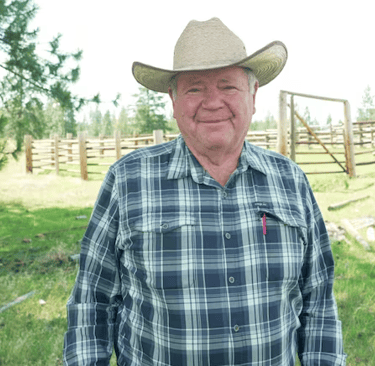

Under the sweeping skies of Elko, B.C., rancher Morgan Dilts watches his cattle graze on Crown land — public property leased by the province for exactly this purpose.

“Our ranch does not exist without it,” said Dilts. “And many, many ranches in B.C. are in the same boat.”

But ranchers across the East Kootenay are sounding the alarm: too much of that public grazing land is sitting unused due to bureaucratic delays, making it harder for new ranchers to get started and for existing ones to grow.

According to Randy Reay, president of the Waldo Stockbreeders’ Association, about 90% of the region’s cattle rely on Crown land. Yet, he says, roughly 4,000 animal unit months (AUMs) — a key measure of how much grazing land is available — are sitting idle. That’s enough to support hundreds of cows for an entire season.

“We’re down to a third of the cattle we once had,” Reay said. “And when grazing land is left in limbo, it’s impossible to expand.”

The leases, which typically last 20 years and cost at least $675 annually, are controlled by the B.C. Ministry of Forests. But ranchers say the process to revive unused leases is bogged down by infrastructure reviews and red tape.

Barriers for New Ranchers

Without access to grazing land, Dilts warns, young people trying to enter the cattle industry face an impossible task.

“A hundred acres doesn’t graze enough cattle to pay the bills,” he said. “Unless you’re born into it and inherit land, you just can’t make it work.”

He and Reay argue that at a time when Canadians are rethinking food security, the province should be removing barriers — not creating more.

“B.C. doesn’t come close to producing the food it consumes,” said Reay. “We need to stop standing in the way of local agriculture.”

An Untapped Fire Prevention Tool

Beyond food, unused grazing land could also be a missed opportunity in wildfire prevention. Cattle help remove dry vegetation — natural fuel for wildfires — and grazing has been used in places like Quesnel and Cranbrook for this very reason.

“It’s dangerous to let once-grazed land sit stagnant,” said Dilts. “It puts homes and livelihoods at risk.”

The Ministry of Forests acknowledges it is using “targeted grazing” for wildfire mitigation but hasn’t provided specific details on where or how often.

Calls for Action

The province says decisions around grazing leases must factor in food availability, wildlife needs, First Nations consultation, and infrastructure like fencing and water sources. But Dilts says failing to maintain these assets while waiting for new lessees makes the land harder to lease — a cycle he says is self-defeating.

“It’s like letting a rental home rot just because it’s temporarily vacant,” he said. “It doesn’t make any sense.”

For now, the ranchers say they’ll keep pushing. What they want is simple: fewer hurdles and faster action to make use of land they believe could benefit not just ranchers, but all of B.C.

“The government needs to step away from the red tape,” said Dilts, “and get into some green lights.”

News

Stay updated with the latest BC news stories, subscribe to our newsletter today.

SUBSCRIBE

© 2025 Innovatory Labs Inc.. All rights reserved.

LINKS