Born in Vancouver, the Peter Principle Explains Why Bad Managers Thrive — and Why the Idea Still Hits Home

Shraddha Tripathy

12/29/20254 min read

Just outside Vancouver’s Metro Theatre, a small plaque commemorates a moment of theatrical disappointment that ended up shaping how the modern workplace understands failure.

In the early 1960s, writer Raymond Hull was standing in the theatre lobby during intermission, venting about a play he found painfully bad. According to the plaque, a tall stranger nearby offered an explanation: the play wasn’t terrible by accident. It was the product of people being promoted beyond their competence.

That stranger was Laurence J. Peter, and the idea he casually outlined that evening would later become known worldwide as the Peter Principle—the notion that employees tend to rise through organizations until they reach roles they are no longer capable of performing effectively.

The conversation sparked a collaboration between Hull and Peter, culminating in the 1969 book The Peter Principle: Why Things Always Go Wrong, a work that skewered corporate hierarchies decades before Dilbert comics and The Office made workplace dysfunction mainstream entertainment.

The book sold millions of copies, entered the business lexicon, and ensured Peter’s name would become shorthand for managerial incompetence.

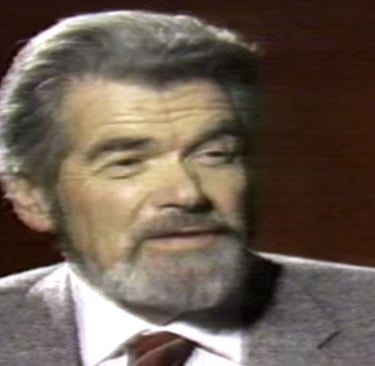

“I’m never sure whether our world is run by idiots who are sincere or wise guys who are putting us on,” Peter once remarked in a later interview, capturing the mix of satire and sincerity that defined his work.

From Classroom to Corporate Satire

Peter was born in Vancouver in 1919 and spent more than 20 years teaching in the city before becoming a professor of education at the University of British Columbia, and later at the University of Southern California.

His observations were rooted not in boardrooms but in schools. In the opening pages of The Peter Principle, he wrote that many teachers and administrators he encountered appeared “incompetent in executing their duties.” Over time, he concluded that promotion itself was often the problem.

“The cream rises to the top,” Peter argued, “until it sours.”

In his view, every position eventually becomes occupied by someone incapable of doing the job well, while actual work continues to be carried out by those who have not yet been promoted into failure.

Though framed as humor, the idea resonated widely—perhaps because it felt uncomfortably familiar.

Does the Peter Principle Actually Exist?

While Peter and Hull intended their book as satire, researchers have since tried to determine whether the principle holds up under scrutiny.

A landmark 2018 study examining more than 50,000 sales employees across 214 firms found evidence consistent with the Peter Principle. High-performing salespeople were frequently promoted into managerial roles—even when their individual excellence did not translate into effective leadership.

One of the study’s authors, Kelly Shue of the Yale School of Management, says the logic behind such promotions is easy to understand.

“Promotions motivate employees,” she explained. “Even when firms know the best performer may not be the best manager, they often promote anyway to reward effort and encourage ambition.”

In a follow-up study published in 2024, Shue and her colleagues found just how difficult it is to escape the trap. Many organizations attempt to predict leadership success by assessing “potential” rather than past performance, often using tools like the nine-box grid—a framework that weighs achievement against future promise.

But that approach introduces new problems.

“When we looked at the data, we saw an enormous gender gap,” Shue said. “Women were receiving slightly higher performance ratings, but significantly lower potential ratings.”

The findings suggest that attempts to fix the Peter Principle can instead amplify bias, replacing measurable results with subjective judgment.

Radical Solutions — and Practical Ones

Some researchers have proposed more unconventional responses. A 2009 study by Italian academics suggested that randomly promoting employees might, in some cases, outperform traditional merit-based systems—a deliberately provocative idea meant to expose the flaws in conventional thinking.

More practically, some organizations have adopted what’s known as a “dual-track” system. Under this approach, high performers can advance in status and compensation without being pushed into management roles they may not want—or be suited for.

Science-driven companies, in particular, have embraced this model, allowing employees to become senior specialists without overseeing teams.

“You can recognize expertise without turning everyone into a boss,” Shue noted.

A Legacy That Refuses to Fade

Today, the plaque outside Metro Theatre—installed by the Vancouver Public Library—describes The Peter Principle as one of the most famous non-fiction books ever written in British Columbia.

Its success was far from guaranteed. The manuscript was rejected by more than a dozen publishers before finally being accepted.

“I thought I had reached my own level of incompetence,” Peter later joked.

Instead, the book became an instant bestseller upon publication in 1969, suggesting that even the publishing industry was not immune to the phenomenon it described.

Peter never believed failure was inevitable. His satire was not cynical, but diagnostic—meant to encourage better thinking rather than resignation.

“The purpose of my books is not to claim I know all the answers,” he once said, “but to turn people toward solutions rather than escalating problems.”

Peter died in January 1990 at the age of 70, just months before the death of Edward A. Murphy Jr., the man behind Murphy’s Law. Both left behind ideas that endure because they articulate a universal truth: systems designed by humans are vulnerable to unintended consequences.

And for those who find themselves promoted—whether by talent, chance, or the Peter Principle itself—Peter offered one final piece of advice, borrowed from humorist James Boren:

“When in charge, ponder.

When in trouble, delegate.

And when in doubt, mumble.”

News

Stay updated with the latest BC news stories, subscribe to our newsletter today.

SUBSCRIBE

© 2025 Innovatory Labs Inc.. All rights reserved.

LINKS