B.C. First Nation Moves Courthouse to Former Residential School Site to Indigenize Justice System

Subhadarshi Tripathy

7/11/20252 min read

In a powerful act of reclamation and justice reform, the Tla-o-qui-aht First Nation has brought the Tofino provincial court onto their traditional territory — and into the former gymnasium of a residential school — as part of a broader effort to indigenize the criminal justice system.

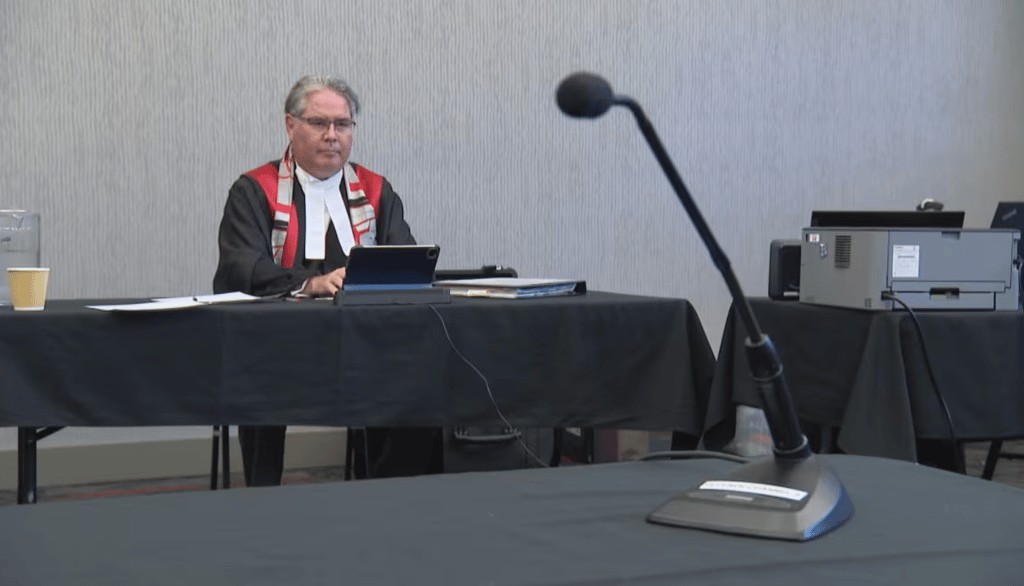

The courtroom, once part of the Christie Indian Residential School, now hosts sentencing hearings and trials in a radically different way: the judge sits at eye level with attendees, proceedings open with Indigenous prayers, and community members — including victims’ families — are invited to speak.

“Too many Indigenous people end up in jail,” said Judge Alexander Wolf, presiding over one of the first hearings in the new space. “When I sentence someone, I’m mindful of their trauma — much of which they didn’t choose.”

The First Nation has an agreement to host the court until at least 2028, with hopes for permanence. All court matters — not just those involving Indigenous people — will be held there moving forward.

A Space Transformed

The courthouse is housed in what was once the gym of the Christie Indian Residential School, a building with a painful past. The school operated from 1900 to 1983, with at least 23 known student deaths. Today, the building forms part of a resort owned by the First Nation and is used for weddings, potlatches, and now, justice.

For some, returning to the building is emotionally complex. “It’s still eerie,” said Thomas George, who attended the school as a teen. “But it’s also healing to use this space for something good.”

George is one of nine members of the Tla-o-qui-aht justice committee, a local body that supports victims and defendants through the legal process. They offer coffee, emotional support, and help families write victim impact statements. In minor cases, they even help arrange restorative justice circles as alternatives to court.

“This changes how our community interacts with the justice system,” said Dezerae Joseph, a project coordinator and committee member. “It makes people feel safe enough to report abuse and seek justice.”

Rethinking Justice

The model is being praised across the province. Kory Wilson, chair of the B.C. First Nations Justice Council, called it “a fantastic, community-led step” and emphasized that every First Nation should have the freedom to build their own path toward justice.

With over 200 First Nations in B.C., Wilson said there's no one-size-fits-all solution — but Indigenous-led models like Tla-o-qui-aht’s are critical to broader reform.

The move aligns with the federal government’s Indigenous Justice Strategy, which calls for a revitalization of First Nations laws alongside reforms to Canada's colonial justice system.

Despite making up only 5% of Canada’s population, Indigenous people are drastically overrepresented in prison. On an average day in 2020–21, Indigenous people were 10 times more likely than non-Indigenous Canadians to be in provincial custody.

Judge Wolf underscored that urgency in his sentencing remarks:

“I don’t want to be here in ten years sentencing someone who hurt your daughter,” he said. “I need you to step up.”

News

Stay updated with the latest BC news stories, subscribe to our newsletter today.

SUBSCRIBE

© 2025 Innovatory Labs Inc.. All rights reserved.

LINKS